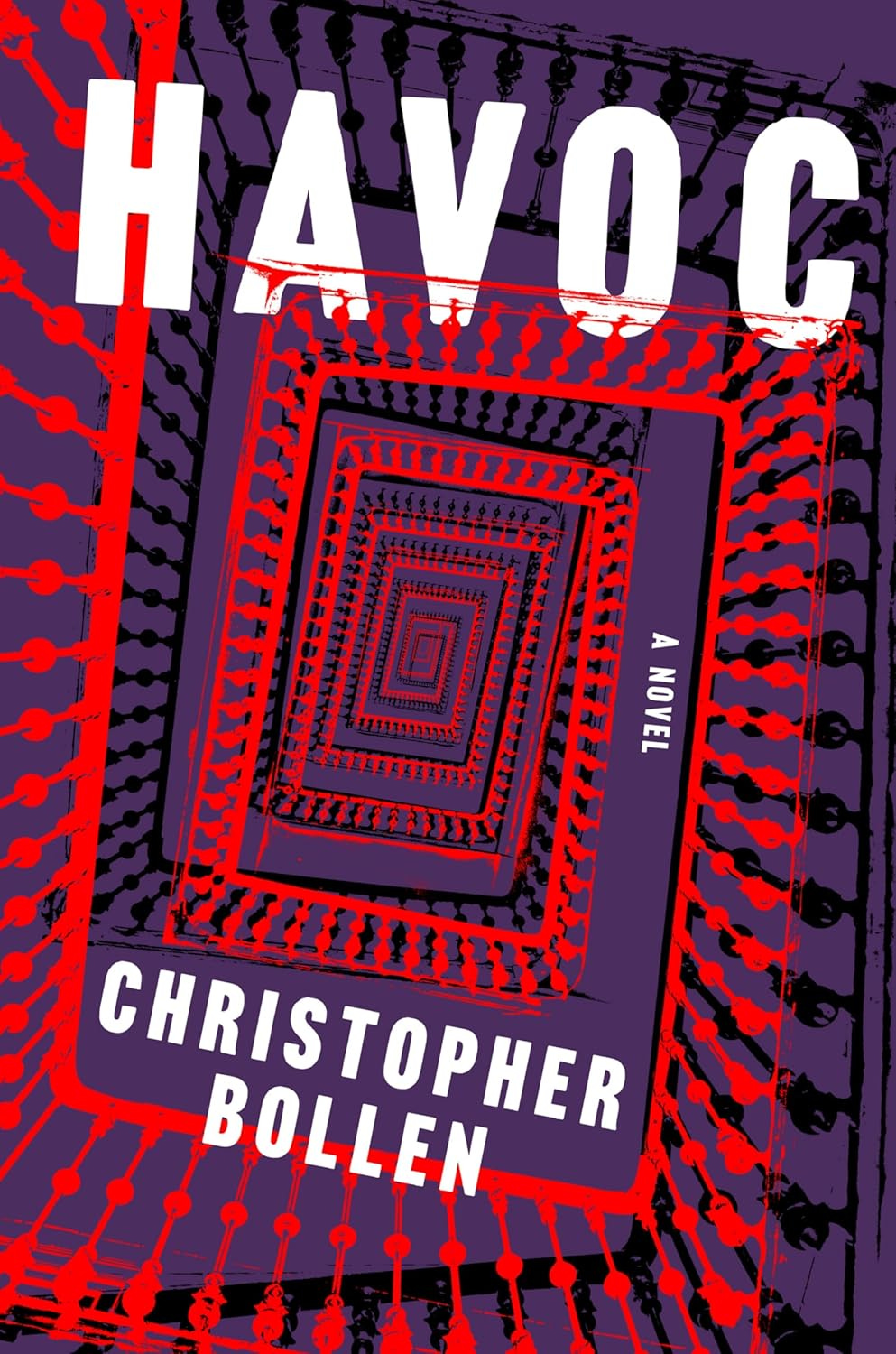

Havoc

By Christopher Bollen

Fiction

Harper

December 2024

An 81-year-old woman's beloved husband and daughter have both died. She is no longer willing to abide her Milwaukee home, and heads for Europe. She finds solace helping people solve the problems in their relationships that she sees, whether they see them or not.

Things are going quite well until the murder.

With Covid closing borders around the world, Maggie Burkhardt escapes Switzerland and lands in Egypt. A once renowned grand hotel in Luxor has become her new home. She considers the manager, Ahmed, a friend. A gay couple are her best friends. Life is going quite well, all things considered.

Until she is caught meddling again. An eight-year-old boy who just arrived with his mother catches her. At first, Maggie thinks she and Otto will become co-conspirators. But she is wrong. Very, very wrong.

In Christopher Bollen's Havoc, Maggie soon realizes Otto has become her nemesis. Not only is he at least as clever as she is, but he also has the advantage of being a little boy who has obviously been sickly. Now the victim of blackmail, Maggie is determined to get her peaceful hotel back and reign as its queen. Otto has no intention of backing down.

The stakes continue to climb higher and higher as their battle continues. Victims start to stack up in acts of retaliation that may lose readers (animals are involved).

Just what in the world is going on? The reader starts to realize how unreliable, and unstable, Maggie is. How much of what she is describing is true? What if it all is? What if none of it is? Bollen, writing through Maggie's eyes, does a masterful job of describing her interior and exterior worlds collapsing. It's not clear until the very end just what is and is not real.

Until that point is reached, Havoc also serves as a way to describe how it feels when a person loses control over every aspect of life. The anger Maggie feels at losing her carefully constructed life is palpable. It screams off the page.

So many aspects of her life are not as she envisioned or thinks should be this way. That includes her long-held view of art. She and her late husband often spend time in museums. He thought she loved it. She hated it. In Maggie's view, that thousands of years of civilization resulted only in a few good chairs and a handful of interesting paintings is appalling.

More worthy of admiration to her are the works of the ancient Egyptians. Especially the artworks created for royal tombs, glorious works of art never meant to be seen by the living.

As the novel loses its veneer of arch Hitchcockian mischief and heads for the darkest of the movie auteur's vision, Maggie's opinions of art, people and how things should be fill in the portrait of who she is and how her world does not meet her expectations.

Viewed that way, Maggie becomes a stand-in for when many people feel things are out of their control, despite their best efforts.